Dovid Tsap, "The Skateboarding Rabbi" weaves together footage of his experiences at skateparks as part of his spiritual journey of self-discovery and transformation through skateboarding. Many more episodes are available.

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Clip: Through the Eyes of a skateboarding Rabbi.29.10.2013

Dovid Tsap, "The Skateboarding Rabbi" weaves together footage of his experiences at skateparks as part of his spiritual journey of self-discovery and transformation through skateboarding. Many more episodes are available.

Thursday, October 10, 2013

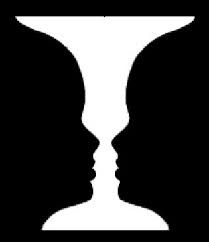

'Face to Face' skateboarding II

...In essence, to come 'face to face' with a

skatepark - or anything/anyone for that matter - is to identify the 'truth' of the thing and to adapt to it. Otherwise one may end up 'back to back': injured, unable to land tricks, or failing to optimise skatepark obstacles. But what is 'truth'? Or, at any rate, how is it

usually defined?

One definition of 'truth' is articulated by Correspondence Theory where a statement is deemed true when it matches reality: I.e. If one points to a green patch of grass and says ‘the grass is green’ the statement is considered true; but if one says ‘the grass is blue’ or ‘the wheat is green’, it is false.[1]

Coherence

Theory considers a statement true when it gels with the network of current knowledge about existence.[2]

Thus, the statement 'Alexander the Great existed' is deemed true not because he

actually existed – as in correspondence theory – but because it coheres with the claims of the vast majority of historians.

Coherence

Theory considers a statement true when it gels with the network of current knowledge about existence.[2]

Thus, the statement 'Alexander the Great existed' is deemed true not because he

actually existed – as in correspondence theory – but because it coheres with the claims of the vast majority of historians.

One definition of 'truth' is articulated by Correspondence Theory where a statement is deemed true when it matches reality: I.e. If one points to a green patch of grass and says ‘the grass is green’ the statement is considered true; but if one says ‘the grass is blue’ or ‘the wheat is green’, it is false.[1]

Pragmatic Theory deems something true if it's of benefit to do so. A

clock (or the belief that clocks exist) is true because it helps people catch trains on time. Truth is created when value is demonstrated.[4]

A tweaked pragmatic theory, Instrumentalism, sees 'a truth' as anything that helps one deal with an ever-changing world. A new condition such as puberty, adolescence, job, marriage, children, relocation, illness, death, etc

- bring challenges. Through effort and the required

skills and resources, however, one commonly finds ways to manage - or even thrive - in the new condition. This is the instrumentalist's 'truth'. Truth

isn't a static thing hiding in the cosmos until found, like a fact before it's proven; it's dynamic; a private or public dance with

the vicissitudes of life.

Of course, an instrumentalist may use other definitions of truth as instruments to deal with life. One might make a statement (I.e. a hypothesis) about a park or one of its obstacles and then validate or falsify the statement through experimentation. Alternatively/additionally, one may research up to date books or watch trick tips to find an approach which is supported by current knowledge or widespread belief among the skateboarding community or other relevant pools of knowledge. Either strategy - and better both in conjunction - can help one find the 'instrument' - the truth - that allows one to skate 'face to face'...

Of course, an instrumentalist may use other definitions of truth as instruments to deal with life. One might make a statement (I.e. a hypothesis) about a park or one of its obstacles and then validate or falsify the statement through experimentation. Alternatively/additionally, one may research up to date books or watch trick tips to find an approach which is supported by current knowledge or widespread belief among the skateboarding community or other relevant pools of knowledge. Either strategy - and better both in conjunction - can help one find the 'instrument' - the truth - that allows one to skate 'face to face'...

[1]

Richards, T.J., The Language of Reason, Pergamon Press, 1978, pp.142-143; see

also Nyberg, David, The Varnished Truth, University of Chicagi Press, USA,

1992, pp.35- 37

[2]

Ibid pp.139-142; The Varnished Truth, 33-35

[4]

Stumf, Samuel Enoch, Socrates to Sartre, McGraw-Hill, 1999, pp.360 - 362

[5]

Ibid. pp.366-368

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

'Face to Face' skateboarding I

Recently, I returned to skate Prahran after almost 6 months and found myself failing to land many of the tricks that I casually land at my home park, St Kilda. It was as if I enthusiastically faced the park, interested to connect with it, but had it turn its back toward me. Soon into the session, however, I realised that the reverse was true: I had my back toward the park.

Recently, I returned to skate Prahran after almost 6 months and found myself failing to land many of the tricks that I casually land at my home park, St Kilda. It was as if I enthusiastically faced the park, interested to connect with it, but had it turn its back toward me. Soon into the session, however, I realised that the reverse was true: I had my back toward the park.

Generally, we make sense of new events or objects in two ways:

a) we draw on memories of similar past experiences or relevant information;b) we distinguish between our memories and the present experience.

For example, when I arrived at Prahran, I immediately started to see the similarities between it and St Kilda. As a result, I skated its mini ramp, quarter pipe, and hip in pretty much the same way that I skate the St Kilda counterparts. After a while, however, I began to identify more and more differences between the two parks: size, surface texture, coping width, transition gradient, etc. This allowed me to fine tune my skating to the parameters of Prahran.

These two methods are akin to the face and back respectively. When one draws exclusively on similarities one only gains a relatively superficial view of a park, seeing it primarily as a shadow of other parks one has skated. It's as though one faces the other, more frequented, parks while having his back toward the current one. In contrast, when one focuses on differences, one gains a more accurate perception of the current park, and really enters into it, viewing it face to face.

The irony is that one seems to feel more motivated and confident to skate a park when focusing on its similarities to other parks one's accustomed. In contrast, when one begins focusing on differences, confidence and excitement levels tend to wane. Hence it appears that the former relates to the face and the latter, the back. In truth however, this difference is on account of two facts:

The irony is that one seems to feel more motivated and confident to skate a park when focusing on its similarities to other parks one's accustomed. In contrast, when one begins focusing on differences, confidence and excitement levels tend to wane. Hence it appears that the former relates to the face and the latter, the back. In truth however, this difference is on account of two facts:- 1. The perception of similarities between things comes quite spontaneously and effortlessly. Differences, however, usually need to be teased out through conscious effort. People are naturally inclined to lose some motivation when they discover that effort and work is needed to succeed.

- 2. Similarities offer an often illusory sense of confidence. Differences, however, sap confidence levels as they reveal that one may still lack the skills to effectively skate the present park.

Monday, July 29, 2013

Saturday, May 25, 2013

Monday, May 20, 2013

Street Dreams

Regardless of the available number and quality of skate parks, skateboarders seem compelled to skate 'Street': to jump stairs and fire hydrants, slide down handrails, assail monuments, grind ledges, and ride walls. This has sparked ongoing confrontations between skaters and authorities, be they security guards, home owners, building managers, police officers or council members. What underlies this obsession with the ‘street’? Here are some possible motivations:

Availability: It may

be suggested that travelling to a skate park takes time and one may not even be

available in some places or at certain times. The street,

however, is readily available.

Availability: It may

be suggested that travelling to a skate park takes time and one may not even be

available in some places or at certain times. The street,

however, is readily available.

Along the way: Many

skaters, especially non-drivers, use their skateboard for

transport and typically have their boards with them much of the time. If they're already skating, surely they'll use the obstacles they encounter on their way.

Although these reasons may explain why people street-skate, they don't explain why

skaters will leave a skate park in order to skate a street spot. The

following explanations try to address this.

‘Stolen waters taste sweeter’: The Talmud explains that people have increased excitement when benefiting from things prohibited to them. Skating a set of

stairs in a high school complex may therefore be more exciting than skating

a similar set at a skate park.

Novelty: Skate parks

are limited in the challenges and obstacles they offer. The 'Street' however, has

relatively limitless opportunities for novelty, experimentation, and adventure.

Novelty: Skate parks

are limited in the challenges and obstacles they offer. The 'Street' however, has

relatively limitless opportunities for novelty, experimentation, and adventure.

Conquest: Many

skaters are also graffiti artists or associate with people so

inclined. 'Writers', as they're called, spread their signature -‘tag’ - in order to make a reputation for themselves in the underground culture and in order to feel that they've 'conquered'

a place by signing it. Many skaters enjoy a similar attitude: knowing that skate spots tend to trigger skaters to recall the tricks landed in those spots, he leaves invisible traces of his artwork in many different places. He may

also feel that he's conquered much territory.

Living 'out of the box': There's something special about viewing and using objects in

unconventional ways, especially in ways unintended by the designers. It’s as if one becomes a co-creator of the object. Thus, when Marcel Duchamp entered a urinal in an art exhibition (which

he called ‘Fountain’) rather than creating anything new, he merely reinterpreted a ready-made item. Still, this opened people’s eyes to the

beauty and art in even the basest objects. Along these lines, skaters may have fun revealing the artistic potential of otherwise ordinary street objects.

Being real: Whether aware of it or not, most people desire to live and thrive in

the ‘real world’. To confront reality as it is without escaping into the

comforts of fiction and fantasy. In this way, one validates himself as being

real.

When skating in a skate park, a skater feels that he is escaping from the real world, entering into a space which is designed for skateboarding, where the ramps, ledges, handrails, stairs, etc., are not real but artificial – in a sense, fictional. The stairs don’t really lead anywhere, one walks up them in order to jump down them. The hand rail is not for holding onto when using stairs, it was made for grinding and boardsliding.

As long as a skater feels he is not skating in the real world, he feels he is escaping from it and thus not being real. This is why many skaters see the skate park as a preparation for street skating: for them, it amounts to flying lessons on a simulator in preparation for actual flight.

When skating in a skate park, a skater feels that he is escaping from the real world, entering into a space which is designed for skateboarding, where the ramps, ledges, handrails, stairs, etc., are not real but artificial – in a sense, fictional. The stairs don’t really lead anywhere, one walks up them in order to jump down them. The hand rail is not for holding onto when using stairs, it was made for grinding and boardsliding.

As long as a skater feels he is not skating in the real world, he feels he is escaping from it and thus not being real. This is why many skaters see the skate park as a preparation for street skating: for them, it amounts to flying lessons on a simulator in preparation for actual flight.

Check out this clip of some New York Street Skating:

Tuesday, May 7, 2013

Saturday, April 20, 2013

Thursday, April 4, 2013

St Kilda Skatepark pre-opening Session

Who could wait for the St Kilda Park to open? Not these skaters:

Sunday, February 17, 2013

Dovid's Authentic Kabbalah books

| The Orchard: Adventures in Kabbalah Only $7.69 |

| Three and Four: Pesach in Kabbalah Only $3.99 |

| Beauty Art and Colour in Kabbalah Only $3.99 |

| Within the Wedding Canopy Only $3.99 |

| An Interaction with Angels Only $3.99 |

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Pascal: Feeling Groovy

I once read a book which explained some of the Hippy slang terms of the 60's and 70's. 'Groovy' was the word that struck me most. Groovy, the book states, implies that as a needle in a record groove enables one to hear music, when one's awareness is completely in the moment - the groove - one experiences reality in the richest ways.

I once read a book which explained some of the Hippy slang terms of the 60's and 70's. 'Groovy' was the word that struck me most. Groovy, the book states, implies that as a needle in a record groove enables one to hear music, when one's awareness is completely in the moment - the groove - one experiences reality in the richest ways. There is one skateboarder who, to me, personifies the notion of 'groovy': Pascal Leniston. When Pascal skates, he seems completely absorbed in the experience. He doesn't grapple with his board, attempt to impress others; nor is he striving to become a pro. Rather, when he skates he reminds me of a young child playing with a toy, relating to the world in a pure and simple way.

.png) When Pascal fails to land a trick, he usually smiles as if to suggest, 'Hey, that was fun too!' And, when he relates some of the amazing tricks he has performed, he stresses how much fun he had performing them rather than drawing attention to his skills or even the 'gnarliness' of the trick.

When Pascal fails to land a trick, he usually smiles as if to suggest, 'Hey, that was fun too!' And, when he relates some of the amazing tricks he has performed, he stresses how much fun he had performing them rather than drawing attention to his skills or even the 'gnarliness' of the trick.Pascal's playful way of skating is also visible in his tendency to bring old school tricks which, as relics, are seldom seen, and seasoning them with a contemporary flavor. (In the clip below, he performs an 'Underflip' off a ledge and onto a ramp.) He also appears to enjoy stretching skate park 'boundaries' for the sheer joy of it. For instance, he may use obstacles in unexpected ways, or literally, skate beyond the officially designated skate park limits. (In the clip, he grinds not only the formal skate park ledge but continues on to the narrow wooden barrier.)

.png)

I once overheard him talking to a few kids at Prahran Skate Park. He was telling them that he remembers being like them, skating all day and dreaming about skating at night. Though he was describing their purity of being and their innocence, he was doing so with such vitality and feeling that it was obvious that a spark of that innocence still glows strongly within him. To me, this was clear testimony, from Pascal's own mouth, that his amazing skateboarding style is largely inspired by sheer fun and play.

Pascal Shredding Prahran (Pascal appears at: 1:21)

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

Street Dreams

1. Availability: It may be suggested that travelling to a skate park takes time and one may not even be available in some places or at certain times, such as at nights. The streets, however, are readily available.

2. Incidentally: Many skaters, especially those that don’t

yet drive, use their skateboard for transport and typically have their boards

with them much of the time. If they are already skating, surely they will use

the obstacles that come their way to perform tricks on and have some fun.

However, though these first two explanations

may be real reasons why people sometimes street skate, they fail to explain why

skateboarders will leave a skate park in order to skate a street spot. The

following explanations attempt to address this.

3. ‘Stolen

water tastes sweeter’: The Talmud explains that

people tend to have exciting pleasure when they benefit from things normally

prohibited to them. Skateboarding a set of stairs in a shopping complex may

therefore be more exciting than skateboarding the same sort of stairs at a

skate park.

4. Novelty:Skate parks are limited in the challenges

and obstacles they offer. The street however, has relatively limitless

opportunities for novelty, experimentation, and adventure.

Many skateboarders have a similar attitude

in the sphere of skateboarding. By skating all sorts of difficult street spots

around his city, a skater may feel that other skaters who arrive at that spot

will recall how he did such and such a ‘gnarly’ trick there. He leaves his

invisible artwork for passersby to appreciate him by. Alternatively, he may

feel as though he partly ‘owns’ the place that he skated, after all, he did

conquer it.

6. Living

out of the box: There is a very special feeling when one

can view and utilize objects in unconventional ways. That is, in a way that

they were not intended to be used by their inventors. It’s as if one becomes a

co-creator by reinterpreting the object. Thus, when Marcel Duchamp entered a

urinal in an art exhibition (which he called ‘Fountain’) he did not create

anything new but merely re-framed a mundane object. Yet, this was deemed

artistic and opened people’s eyes to the beauty inherent even in the basest of

objects.

Along these lines, skaters have incredible

pleasure in perceiving and revealing the artistic potential that otherwise lies

hidden within banal street objects.

As long as a skater feels he is not skating

in the real world, he feels he is escaping from it and thus not being real.

This is why many skaters see the skate park as a preparation for street

skating: for them, it amounts to flying lessons on a simulator in preparation

for actual flight.

Thursday, January 10, 2013

Dance, Acrobatics, and skateboarding

Another central feature of both dance and acrobatics that distinguishes them from

ordinary human movement is the precarious positions assumed by performers in

relation to gravity. For instance, dancers raise their legs to awkward angles,

fall forward or backward, spin or rotate in the air, or simply assume awkward foot

stances. The magic is that they maintain perfect balance and grace. In

contrast, in ordinary human movement, people attempt to maintain the most

stable and safe postures possible, in particular, those requiring least effort

to maintain.

Acrobatics,

however, goes further in the degree of instability that it expresses.

Typically, the acrobat is performing movements which so significantly defy

gravity that danger of physical injury is constant. Hence, whereas spectators

hold their breath while watching acrobats perform somersaults and mid air

rotations of sorts, and feel relieved when the acrobat safely completes his

routine, spectators of dance typically lack such fearfulness. Skateboarding, like

acrobatics, has a considerably higher level of instability and danger relative

to dance.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)